Bridgeport is about 10 or so miles from Brewster depending on which road you take today, but when the Great Northern Railroad laid their track from Oroville to Wenatchee through Brewster and Pateros in 1914 – bypassing Bridgeport all together – this distance might as well have been 100 miles. Especially so when trying to transport hundreds of crates of apples from packing warehouses in Bridgeport and the Bridgeport Bar to market. This was the context for one description of packing operations in and around Bridgeport during the 1920s from the late Warren Monroe (Quad City Herald August 28, 2009).

Warren remembered that packing warehouses were located along the riverbank in the Bridgeport area and that by using a pulley system to transport boxes of apples to barges they could be shipped down river to market (see figures below). Warren remembered, “They loaded (fruit) on the boat and went to Pateros most of the time. Sometimes they’d take it all the way to Wenatchee.” For the Monroe family in Bridgeport, the late-1920s marked the beginning of their well-known ownership of the “Siwash” brand of packed apples – but to understand the Siwash brand and the development of the Monroe-Slade Fruit Company orchards, we must step back to Brewster, a Mr. “L.H.” and Mrs. Anna Spence, the Columbia-Okanogan Orchard Company, and Buster Brown.

Local newspapers documented that in the spring of 1911 a Mr. and Mrs. Spence purchased property between Brewster and Bridgeport, along what is known as the Bridgeport Bar. According to a 1926 article in the Brewster Herald (January 1, 1926), the Spence’s were told by many growers and neighbors in town that this portion of land could never produce apples because it required pumping water vertically, 200 feet up from the Columbia River to their orchards on the Bar, and that pumping water this height and distance was thought impossible. That did not deter the Spence’s. They found a “pump man” who said it could be done, and they installed a pump which did indeed bring water from the Columbia River to their orchards along the Bar. The Herald amusingly reported that when they began planting their apple orchards in 1911 neighbors came by and asked where they were going to get water to irrigate the trees, to which Mr. Spence would, “cast a longing glance at the river below and say ‘there’s the river’.”

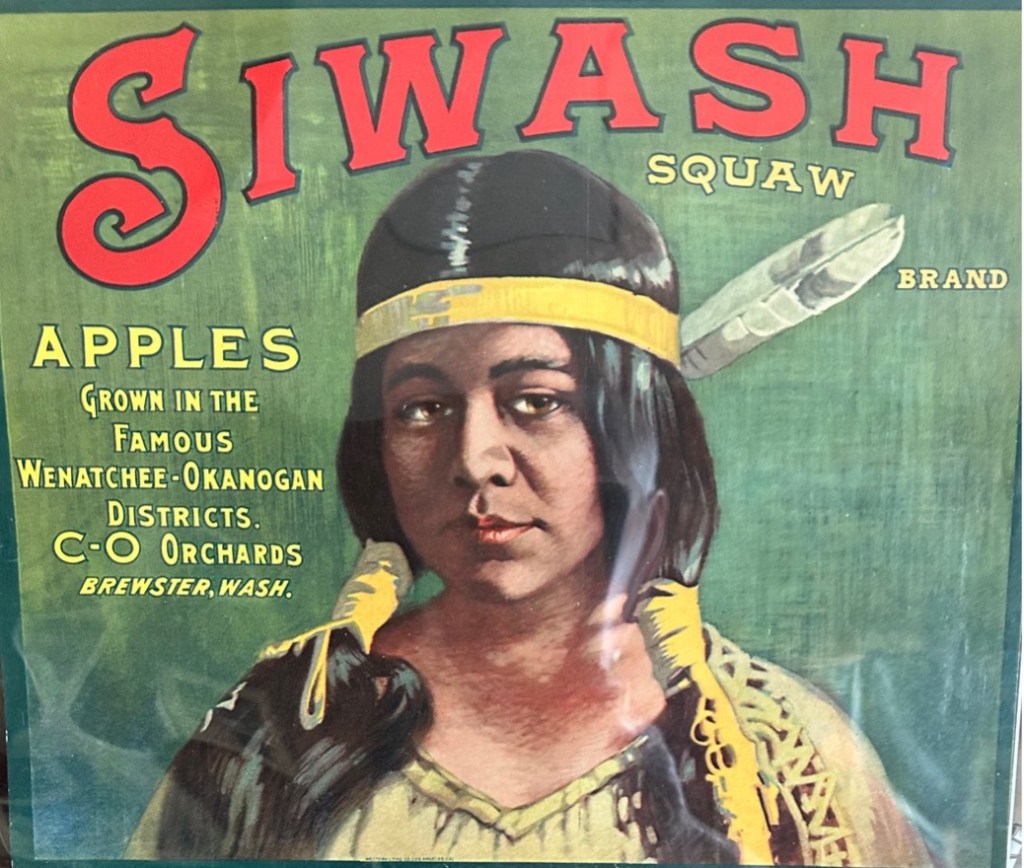

Through experimentation and some hand-irrigating with buckets, the Spence’s eventually got their pump station constructed and working properly in 1913. Apple trees flourished. By 1915 they were able to pick apples from their trees and by 1925, only ten years later, thousands of boxes were being picked and packed from the orchards as reported by the Herald. For example, in the fall of 1925 Mr. Spence was the largest reported red delicious grower in the Brewster District having packed and shipped 44,000 boxes to eastern U.S. markets (Brewster Herald October 23, 1925). His Columbia-Okanogan Orchard Company (or “C-O Orchards”) was selling under a brand name called “Siwash” and in 1925 Mr. Spence had shipped his 44,000 apple boxes from the Bridgeport Bar to Brewster on his boat the “Siwash” (see figure below). It reportedly took 32 round trips to transport apples to the railroad that year alone.

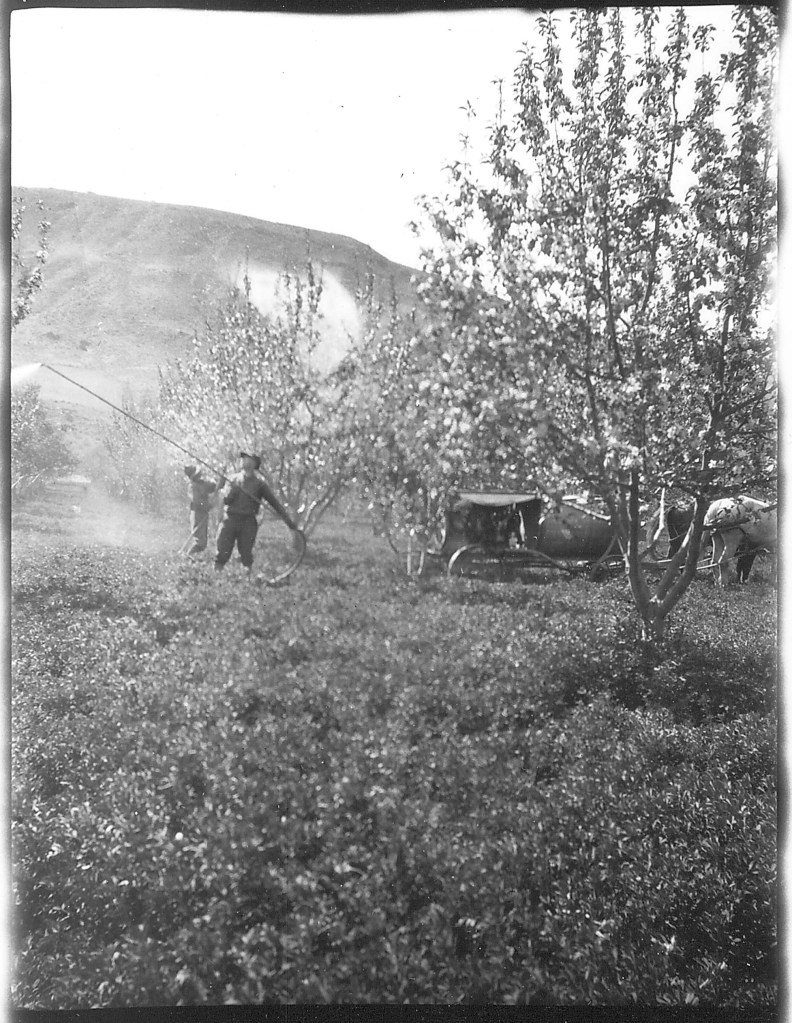

One reason the Spence’s had such successful orchards was due to their high risk, but apparently high reward, gambit at irrigating directly from the Columbia River. While they did have to hand water their apple trees with 5-gallons of water per-day in the early years, by 1926 they were pumping 2,000,000 gallons of water to their orchards every 24 hours. In 1926, the Spence’s estimated 100,000 boxes would be picked, 70% of which were red delicious apples. Their orchards employed 150 men and thinning alone cost $5,000 in 1925-1926 (which is roughly $89,000 today).

Based on reporting at the time, the Spence’s also had one of the most successful and technically advanced orchard operations which helped facilitate a remarkable growth and sale of apples in the eastern U.S. The Brewster Herald finished their summary article with clear praise:

The Spence “Siwash” brand can be depended upon to be what the label says it is. It will be packed a little better will look a little neater and the buyer can find a little quicker sale and none better. The apples are of the highest quality, because of this system that has made the “Siwash” brand a by word in the apple consuming homes of the east, and it also spells with the full meaning of the word “Par-Excellence”.

But tragedy struck the Spence’s in May 1929 when L.H. Spence died, at age 56, in Seattle after suffering through a 10-month illness. According to public census records and Mr. Spence’s obituary, he and Anna had no children or descendants, and Anna leased the orchards immediately after his death.

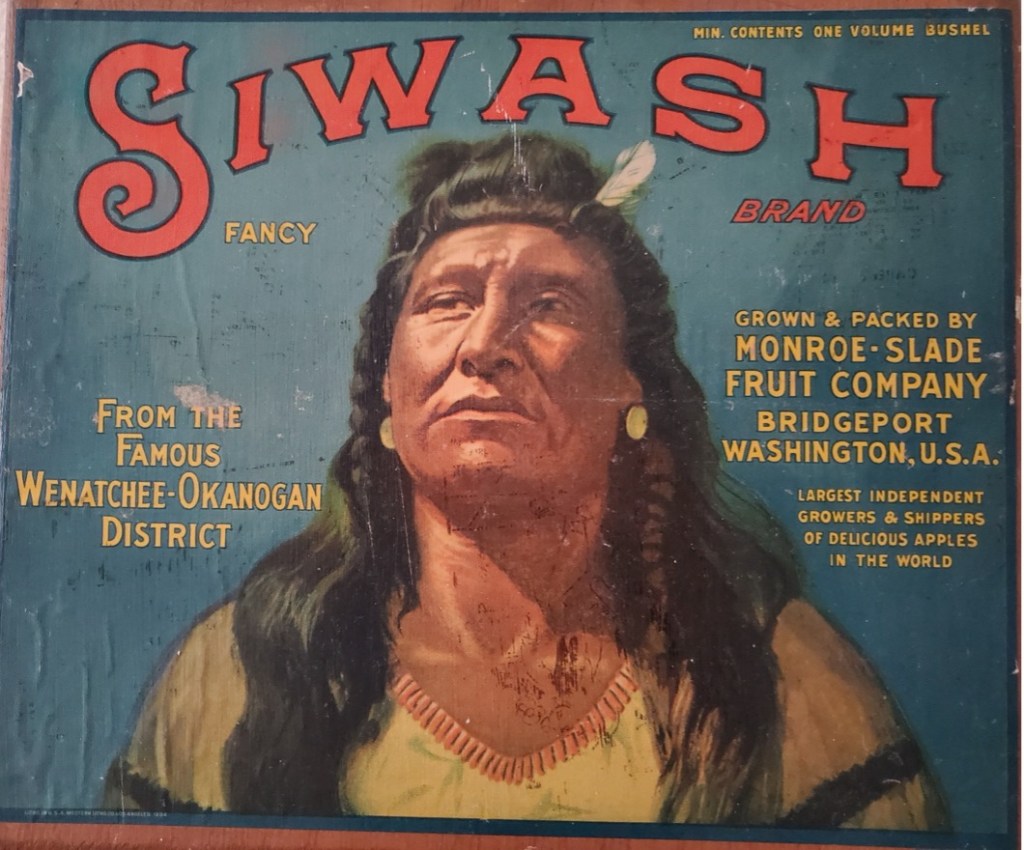

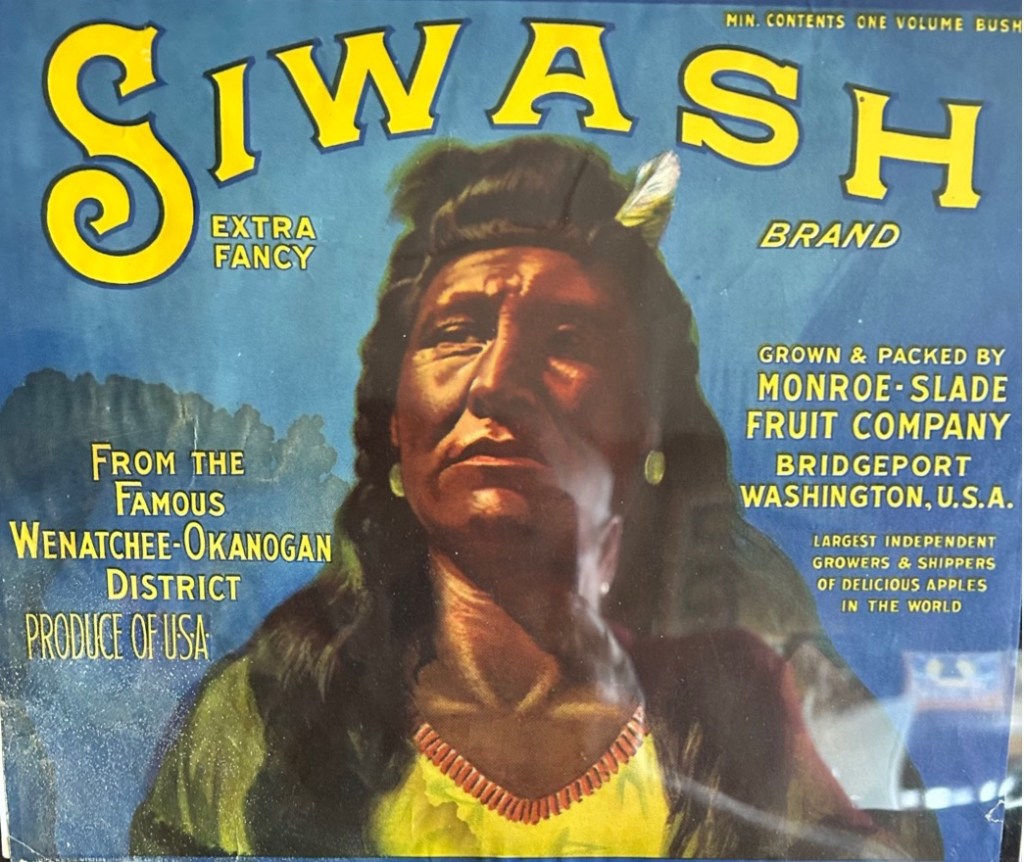

A variety of C-O Orchard brand labels were produced and advertised during the ~18-year period of their operation and ownership by the Spence’s. These included the “Tepee” and “Siwash” brands, among others (see below). One label, reproduced in the Yakima Valley Museum’s volume (16) shows a river and orchard scene stretching into the background with a large, white, “C-O” printed over the top of the scene, the brand being described as “Columbia-Okanogan Orchards, Brewster, WA”. Importantly, each of these labels clearly indicated some form of C-O Orchard marketing and ownership – this is important considering what occurred immediately following Mr. Spence’s death.

Thanks to Warren Monroe’s daughter, Shanta Gervickas, and an interview she helped facilitate with Warren’s surviving brother, John Monroe, along with numerous newspaper articles and other references from throughout the 20th century, after the death of Mr. Spence, C-O Orchards were quickly leased to other growers. Warren Monroe remembered that the Spence family did not want to continue orcharding – likely because Anna Spence was the only family member remaining – and that the Monroe boys (more on them below) quickly began leasing the property. John Monroe remembered it similarly, the C-O Orchards were going to go out of business so the Monroe boys along with their brother-in-law, Stanley Slade, purchased a lease on the C-O Orchard Company brand and their orchards along the Bridgeport Bar.

The “Monroe boys” – as they were known – and their family and descendants have a long orcharding and business history in Bridgeport and throughout north-central Washington. The “boys” themselves were the sons of John Will and Laura Amos Monroe from Hart County, Kentucky. There were five boys and two daughters in total, Carl, Vernon, Sterling, Raleigh, Leonard, Nell and Sue. Raleigh’s children included Warren, John, Dean, Don, Jean, Roberta and JoAnn.

It is important to note here that while Warren’s daughter Shanta Gervickas, and Warren’s brother, John Monroe, both provided information as part of this research, their late cousin Shirley Monroe Bennett also published a family history in 1989 titled Freck. Shirley Monroe Bennett was Vernon Monroe’s daughter and “Freck” was the nickname for Vernon. Vernon and Raleigh were brothers. Freck includes numerous pieces of information that help describe the Monroe family experience in Bridgeport and along the Bar during the 20th century and unless specifically cited differently, is the primary referenced used for all descriptions below. These records help describe the Monroe family history in the Bridgeport area prior to and after leasing the C-O Orchards.

In 1911, as the story goes, John Will Monroe (the father), along with his sons Vernon and Carl, joined a group of local men from Auburn, Kentucky, working for a Mr. Charles Crewdson, who were headed to new lands in Washington to begin work clearing sagebrush and planting apple trees. These new lands turned out to be the Bridgeport Bar. During their first summer, Vernon Monroe sunburnt and blistered so badly that by the end of the summer he was covered in freckles, and was given the nickname “Freckles”, or “Freck” (the Monroe family had a long tradition of nicknames, and each of the brothers eventually was known by their nickname).

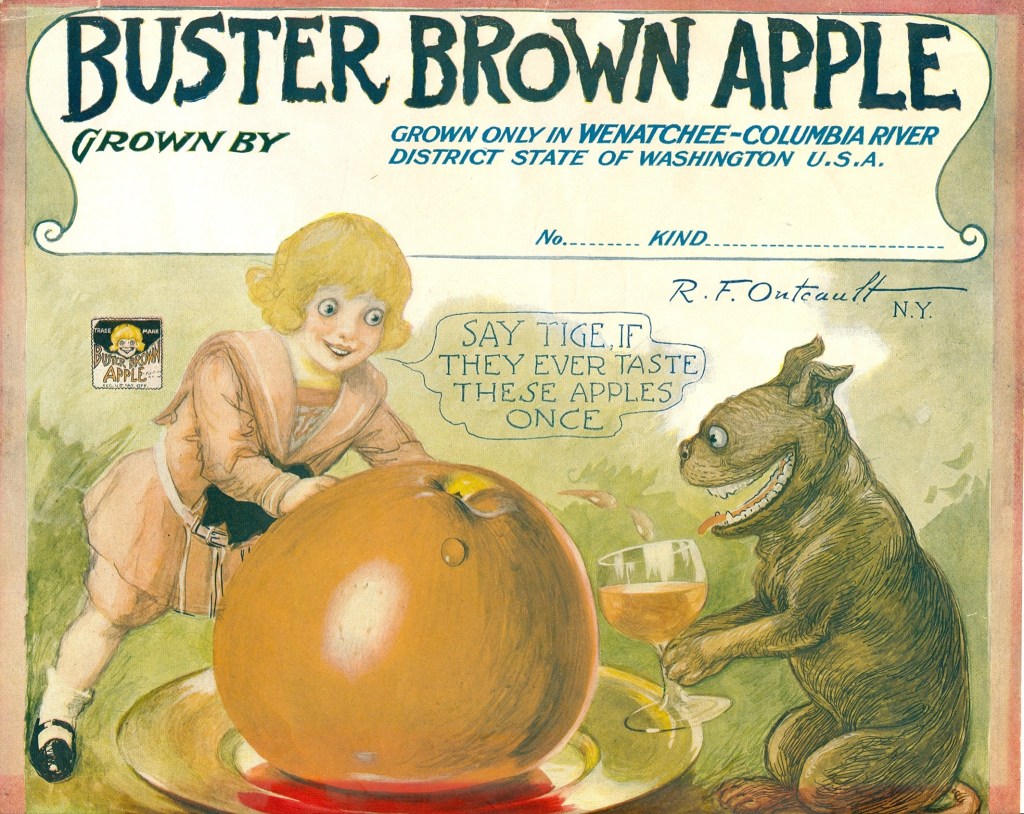

For John Will Monroe and his sons, working for Mr. Crewdson was an important aspect of their family history because as the Brewster Herald reported on July 1, 1911, a “Charles N. Crewdson, representing the Outcault Advertising Company of Chicago, was in the city during the week,” and that he, “is the holder of some valuable realty situated on the Bridgeport Bar, as well as Mr. R.F. Outcault the originator of the ‘Buster Brown’ advertising matter.” The Monroe’s began their work in apple orchards working for the famous Buster Brown orchards and warehouse. Apparently, one of Mr. Crewdson’s wealthy friends in the eastern U.S. included Richard Outcault who was the famed comic artist who created the “Buster Brown and His Dog Tyge” cartoon and apple label for the company. Crewdson and Outcault choose the Bridgeport Bar for their orchards.

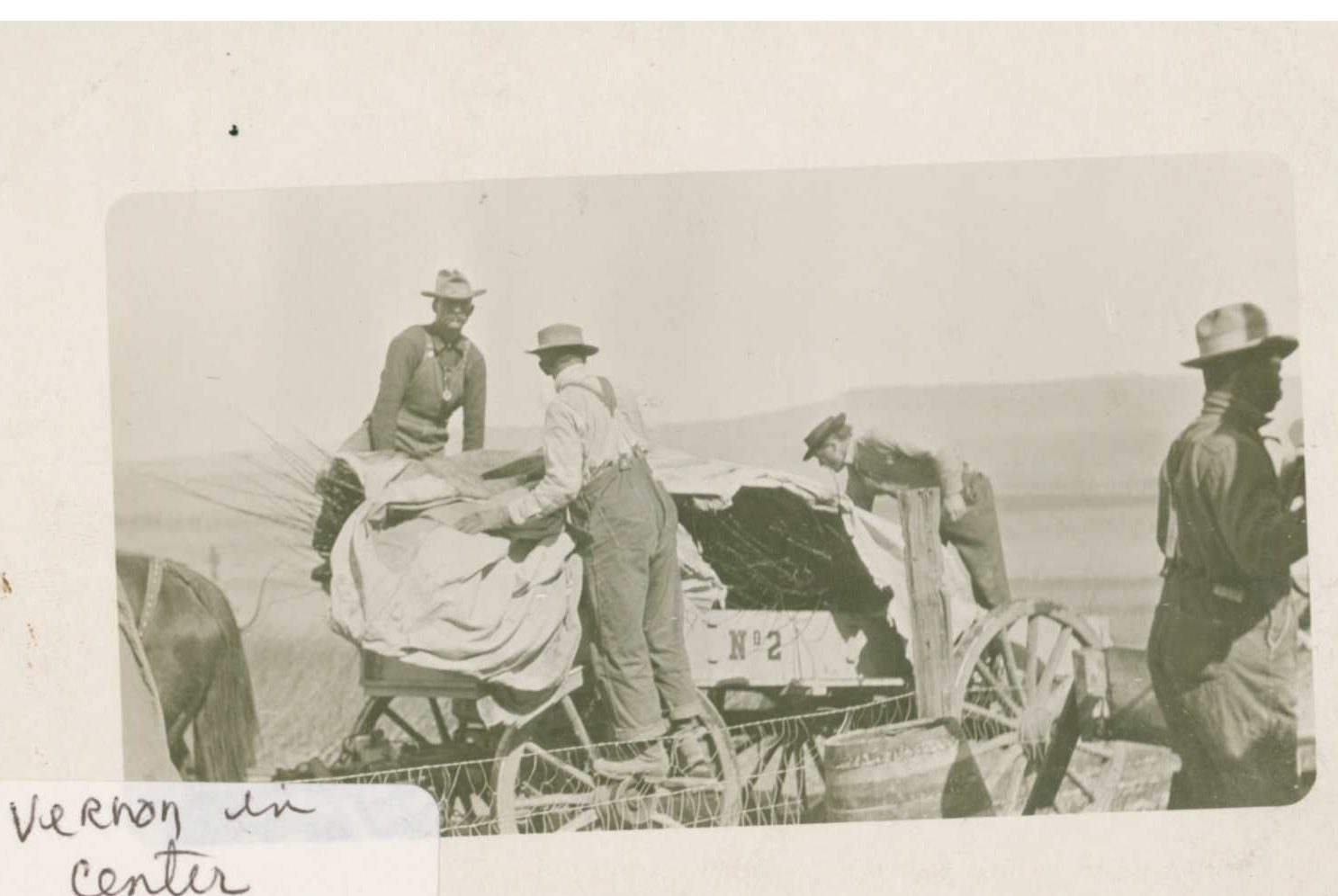

In fact, during their first summer working on the Bar, Shirley Monroe Bennett wrote that her dad Vernon met new friends, including his future wife Maude Galbraith, and played baseball at the Buster Brown baseball diamond which was located, “one-half mile south of the Port Columbia steamboat landing, on the west side of the road where Dan Gebbers now has his Granny Smith orchard.” After returning to Kentucky over the winter of 1911-1912, Vernon returned to the Bar during the spring of 1912. He continued to work for Crewdson and Outcault as part of the Buster Brown orchards. The company built several structures throughout Bridgeport and the Bar including a packing shed along the river and a two-story bunkhouse for workers. The bunkhouse is where Vernon lived (see figure below).

Eventually, by early 1915, Vernon was offered a position to manage and live at the Outcault house, farm and orchards along the Bar. He was paid $50 per month for this work which translates to approximately ~$1,557 today – a large sum for the time. Vernon and Maude were married shortly afterwards. Shirley Monroe Bennett, when writing about this time for her father, also noted that Nell Braker (related to Sid Braker, see Growers section) told her that during those days she, “rode horseback to the Buster Brown warehouse to pack apples by lantern light, as there was no electricity then.” Another memorable experience was related by George Braker who was managing the Buster Brown warehouse when World War I ended in 1918. Apparently, when news arrived that the war was over Braker, “shut down the grader and yelled, ‘The war is over!’ Everyone cheered–then the grader was turned back on.” It was packing season, after all!

Vernon and his youngest brother Leonard (known as “Jab” or “Jabo”) leased an orchard owned by E.T. Nichols during World War I as Nichols had been drafted. They eventually bought their own separate orchards and properties during the war as well. By 1920 Vernon had constructed a packing shed on his new orchard property. It was a notable event because when the warehouse was finished, the Monroe’s held a dance in it for everyone in town and “everyone would take their little children, who would play until they got tired; then their parents would bed them down on some apple boxes and go on dancing, sitting out occasionally on an apple box.” Vernon Monroe likely sold his apples under the “Idol” brand as part of the “Monroe Fruit Company” during this period. One “Idol” brand label has a known printing date of 1926 (17).

Before continuing with the Monroe family story however, a brief note is required to explain their fascinating connection to Buster Brown. While the Buster Brown brand and label originated in Bridgeport and the Bar, their orchard company clearly marketed the brand to other growers for their advertisement and distribution. For example, in 1912 the Cashmere Valley Record reported that Mr. M. Horan of Wenatchee sold his entire apple crop to the “Wenatchee-Columbia Fruit Company” (i.e., Buster Brown orchards) for sale and distribution. The version of the Buster Brown label printed in the newspaper included the standard text known on the label today, “Grown By”, with the addition of “M. Horan Wenatchee, Wash.” (see figure below). The version of the Buster Brown apple label present in the Yakima Valley Museum volume (see 16) does not include “M. Horan”, nor does the label version with a printed date stamp of 1915 (see 17 and below). The label reproduced in Freck also does not include “M. Horan”, suggesting that this was an entirely different version of a marketed label for Buster Brown.

Less is known about the Buster Brown orchards, but Richard Outcault died in 1928. The orchard warehouse was also destroyed in a 1923 fire, as described by the Pateros Reporter (July 13, 1923):

“The big warehouse owned by the Buster Brown fruit company, on the river bank at Bridgeport bar, was entirely destroyed by the fire Monday night causing a loss estimated at $30,000. This was one of the finest warehouses in the north country and was equipped for packing out 150,000 boxes of apples each year. Some of the famous men of the country are connected with this gruit company, among them being Frederick Outcult [sic], the great cartoonist, the creator of Buster Brown, Mary Jane and Tiger; Chas N. Crewdson, author and salesman, contributor to the Saturday Evening Post and other magazines; Chas G. Shedd of Chicago…banker and business man, and many others. The fire not only destroyed the building but also grading machines, paper, boxes, etc., that were stored in the building.”

Which is all to say that the Buster Brown orchards and brand – one of the most famous apple labels from the Pacific Northwest – clearly began on the Bridgeport Bar and was eventually marketed to other orchards and growers in the Wenatchee-area. Most importantly, the Monroe family was right there from the beginning.

Now we can return to Siwash.

Although Vernon transplanted to Bridgeport and the Bar relatively quickly after his first couple of years splitting seasons between Washington and Kentucky, the remainder of the Monroe family, including their father John Will and the rest of the “boys”, did not make a permanent move until 1917. When they did permanently move to Bridgeport in 1917, John Will Monroe had a position at the Chicago Orchard Company working for a Mr. Fred Ham (the Chicago Orchard Company appears to be a separate orcharding operation from the Buster Brown orchards, but this detail is slightly unclear).

Two of the Monroe boys, Sterling and Raleigh, enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War I as part of the medical corps. But since Vernon and Leonard had families and orcharding businesses, they did not. Raleigh wanted to pursue a career as a doctor and was attending the University of Washington when the U.S. formally entered the war. Although he served in the medical corps during the war, by the time of his discharge in 1919 he was convinced by his brothers to return to the Bar and continue apple growing and was unable to finish his degree.

It was Leonard and Raleigh (also known by his nickname, “Friday”) who joined with their brother-in-law in 1929 to lease and buy the Spence’s Siwash orchards. They began selling under the “Siwash” brand as part of the Monroe-Slade Fruit Company. When their company began leasing the “Siwash” brand and orchards they made slight modifications to the Spence’s apple labels (see below). While the overall imagery stayed the same, they included a block of text stating “Grown & Packed By Monroe-Slade Fruit Company Bridgeport Washington, U.S.A.” with an additional note that they were the “Largest Independent Growers & Shippers of Delicious Apples in the World”.

Raleigh’s son John shared that the family orchards after 1929 were typical for that time in that they planted, grew, and sold Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, Jonathans, and Winesaps across the Bar – but the orchards were prolific, especially because they included the Spence’s successful red delicious. Shirley Monroe Bennett shares one particularly telling story in Freck:

About 1932 or 1933 we had an early winter and they had 80,000 boxes of Winesaps on the trees with many more Winesaps and Delicious on the ground in boxes. Storage was very scare in the area. They put the frozen boxes in the Bridgeport gym to thaw out so they could be sorted. The weight of the boxes broke the foundation of the gym, and they had to restore it in the spring. [Raleigh] even stored some packed boxes of apples in his front room at that time.

Like the Spence’s experience before them, the Monroe-Slade orchards were forced to transport boxed apples by steamer to the railroad in Pateros or Wenatchee (see figure below), but eventually this transitioned to transportation by truck with the construction of bridges across the Columbia River and Okanogan River, especially after World War II. One historical photograph archived in the Wenatchee World visualizes the juxtaposition of these eras quite well (see second figure below).

The Monroe-Slade Fruit Company was impacted by the same events which struck the Methow Valley, Pateros and Brewster, especially the flooding of 1948, and the construction of Wells Dam in the 1960s. But, on February 2, 1940, tragedy struck when the entire “Siwash Orchards Company” cold storage warehouse caught fire and burned to the ground (Brewster Herald, February 9, 1940). Estimates at the time indicated the fire caused $75,000 in damage (approximately $1.65 million today), including 18,000 boxes of apples. One employee at the warehouse, Don Ernsberger, was eating lunch when he reportedly thought he felt an earthquake, only to discover that an explosion had blown out the compressor room wall resulting in a fire throughout the facility. Investigators suspected that a large circulating fan helped spread the flames. Unfortunately, insurance only fully covered the loss of the apples, just 50% of the equipment and 25% of the facility itself. It was described as a near total loss.

There are two interesting aspects of this event. First, the fire was clearly a significant time for the Monroe family and survives in stories up to today. Warren Monroe remembered that the fire occurred in 1948, but it is likely that was a mistake given that the flood in 1948 also impacted orchards along the Bar. Warren noted that after the fire – since the roads and transportation were better – the family began hauling their apples to the Methow-Pateros Growers cooperative in Pateros for storage and sale as part of “Wenoka” (see Cooperative section).

But second, the Brewster Herald reported that the storage building and equipment was technically property of R.A. Downing (see Growers section) and Fred Furey as part of the “Siwash Orchards Company”. The newspaper further reported that many of the apples were also co-owned by Downing and Furey, but also “other orchardists on the bar.” It is likely that some of the apples stored at the warehouse were owned by the Monroe-Slade family, but not all. Raleigh’s surviving notes, transcribed in Freck, help explain what happened during this period and why the “Siwash Orchard Company” was not owned by the Monroe family by 1940.

Several events transpired when Mr. Spence died in May 1929. By January 1930 the Monroe-Slade was in extensive negotiations with Mrs. Spence about leasing the orchards and brand, but they required an initial investment of $50,000 (nearly $1,000,000 today) and it was being loaned from small, local banks, which Raleigh noted was greater than the legal amount they were allowed to loan at that time. Remember, the Great Depression also began in 1929 and while it took some time to feel the effects locally in Washington state, banks were a different matter.

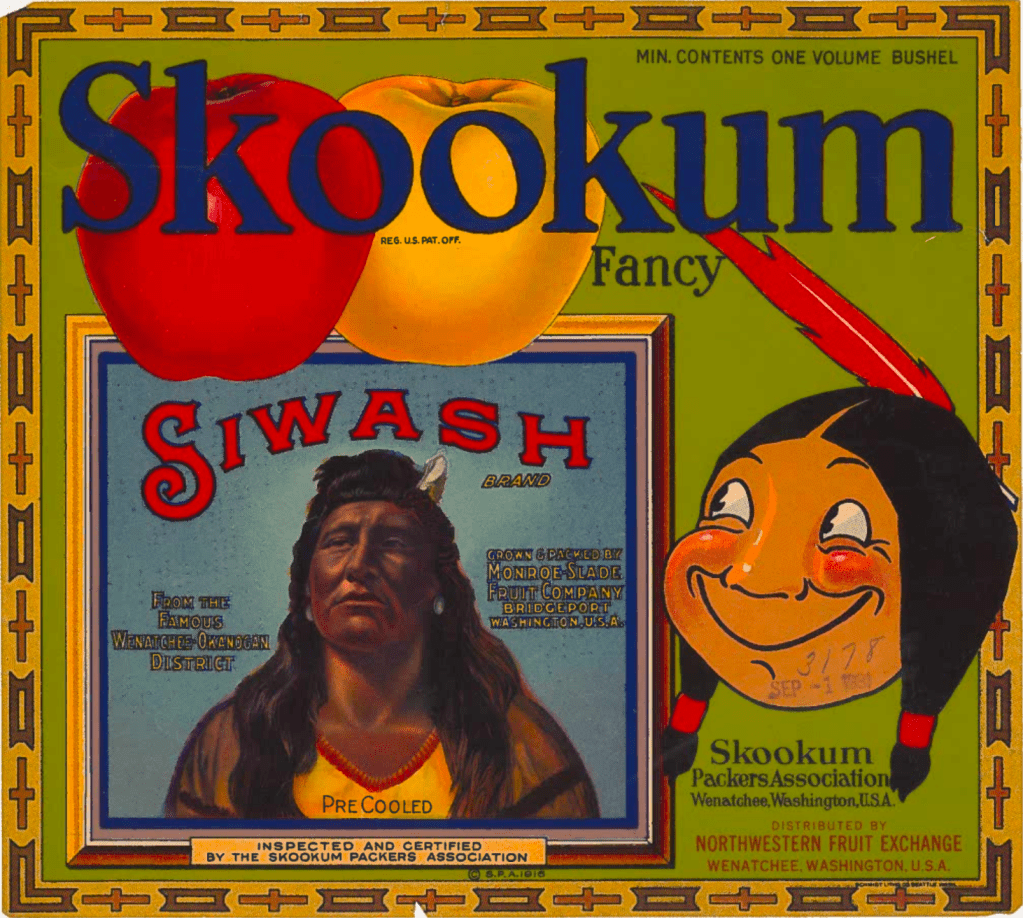

Initially, Raleigh noted that they were able to work with the Northwest Fruit Exchange (i.e., Skookum; see Cooperatives section) to finance the loan for 1930 and 1931, but in 1932 Northwest Fruit Exchange reneged on their contract and did not continue financing. The Monroe-Slade Fruit Company was able to scrape together funding through other government support programs created during the Great Depression for 1932 and 1933, but they were not able to make all payments because of the Northwest Fruit Exchange’s decision. Raleigh described two things that caused this to occur between 1930-1931. While the Monroe-Slade family was under contract with the Northwest Fruit Exchange for financing, they were not under contract with the Skookum Packers Association to market, sell and distribute Siwash apples as part of Skookum. Because the Monroe-Slade family wisely leased the Spence’s orchard operation and brand due to its enormous success and profit (boxes of Siwash often sold for higher rates than other apples), they were on track to pay back, in full, the Northwest Fruit Exchange loan. Siwash was a known and recognizable brand that had a stable, and robust customer base throughout the east coast. This did not sit well with the Northwest Fruit Exchange because they would lose their leverage over the Monroe-Slade Fruit Company and the Siwash brand – thus, they essentially withheld funding to force the family to enter a contract to formally join “Skookum” so that Skookum could sell Siwash branded apples. A Skookum label with a Siwash inset (see below) has a date stamp of September 1, 1931, matching this record.

Raleigh wrote:

The Exchange then notified the Siwash customers that they now had the Siwash label and that in the future they could buy the same fruit under the Skookum label. We bitterly protested their actions in this connection, to no avail; we were under their thumb and they pushed as they pleased; they destroyed Siwash in the markets just as they set out to do, and our apples became just apples.

Raleigh continued:

Leonard Monroe attended the International Apple Shippers convention in West Baden, Indiana, in 1931 and reported that Exchange displayed NOCOR (see Growers section), BLUE GOOSE, and SKOKUM, but no SIWASH; that a number of our old customers came to him stating that they had built up a trade on Siwash and that it was going to be a serious loss to them unless they could get Siwash. Leonard contacted GC of Northwestern, who was also attending the convention, and asked him what this was all about – why couldn’t our old customers get our fruit and our label? Mr. C reluctantly stated that if there was sufficient demand some cars could be shipped under Siwash. Their resistance and refusal to ship under Siwash finally completely destroyed all commercial value of the brand which we valued so highly and which had cost so many of thousands of dollars to establish and put on the market. We figured in purchasing the Spence properties that at least $50,000 was being paid for the Siwash Brand. Many orders came into Exchange specifying Siwash Brand they substituted Skookum. Sometimes when fruit was received, demand would come back to either Exchange or ourselves to send Siwash labels so they could relabel.

After 1933, the Monroe-Slade Fruit Company ownership and leasing of the Spence orchards and Siwash brand ended.

Monroe-Slade ownership had lasted for approximately three years, between 1930-1933. Shirely Monroe Bennett noted that they let the orchards go back to Mrs. Spence at this time. Between 1930-1933 the family had also bought and owned the Wakefield orchard north of Monse along the Okanogan River. They operated it for several years but sold this orchard around 1933 as well. The Monroe-Slade Fruit Company took the packing and grading equipment they had purchased and owned during this time and built their own packing shed in Bridgeport near the Columbia River. Leonard and Raleigh also leased an apple warehouse storage facility in Duluth, Minnesota, for several years in the early 1930s to support the sale and distribution of their brand, but it is unclear if this supported Siwash or their own Monroe-Slade Fruit Company apples. In 1954, Raleigh died, and Warren Monroe remembered that since the orchard business was not doing well and Siwash orchards were long gone from the family, Raleigh’s established the “Siwash Corporation” with equal shares for all his children as part of his will. This corporation managed the various family real estate and orchard properties up until 2009.

Remembering now the warehouse fire in 1940 and the “Siwash Orchards Company” co-owned by Downing and Furey, it is likely that by this point the Siwash brand was not leased or operated by the Monroe-Slade Fruit Company. That suggests that one final known version of the Siwash apple label (see figure below) that has a marketed branding for the “Siwash Fruit Co.” may be part of the post-1933 ownership of Siwash, perhaps by Downing and Furey or others. The historical records available do not exactly clarify the company name discrepancy, but it appears likely that this version of the label was not associated with the Spence’s or the Monroe-Slade family.

While it is unknown to me at this point what eventually happened to the original Siwash orchards and brand, I suspect that the creation of Wells Dam and flooding along the Columbia River may have impacted the brand (similar to the Starr Ranch orchards south of Pateros; see Growers section). John Monroe remembered that when the dam was built and portions of Bridgeport and the Bar flooded, the government condemned the land and gave pennies on the dollar in compensation – then, surprisingly, when flooding did not impact all areas equally and some orchards and lands remained above the new water line, the lands were not returned to their original owners. It is likely that the end of Siwash as a brand occurred at some point during this time in the 1960s, but future research will help untangle this final aspect of the story.

The follow represents the dates and ownership of the Siwash brand of apples:

- 1911-1929 – Spence, Columbia-Okanogan Orchards

- 1930-1933 – Monroe-Slade Fruit Company

- 1933-???? – Downing and Furey, Siwash Orchards Company or Siwash Fruit Company

What is clear from the history of the Monroe-Slade Fruit Company and their family is that they had a tremendous impact on the history of apple growing and orcharding in Bridgeport and the Bridgeport Bar. While not all the Monroe family members were growers, they certainly all helped contribute to the legacy of Bridgeport’s orcharding history. Warren Monroe’s interview with the Quad City Herald concluded it well when remembering that the family was raised with love and respect for each other and helped each other whenever it was needed. Their legacy continues on today in Bridgeport and elsewhere.

If you have any suggested revisions or additions, please email: cylerc [at] gmail [dot] com